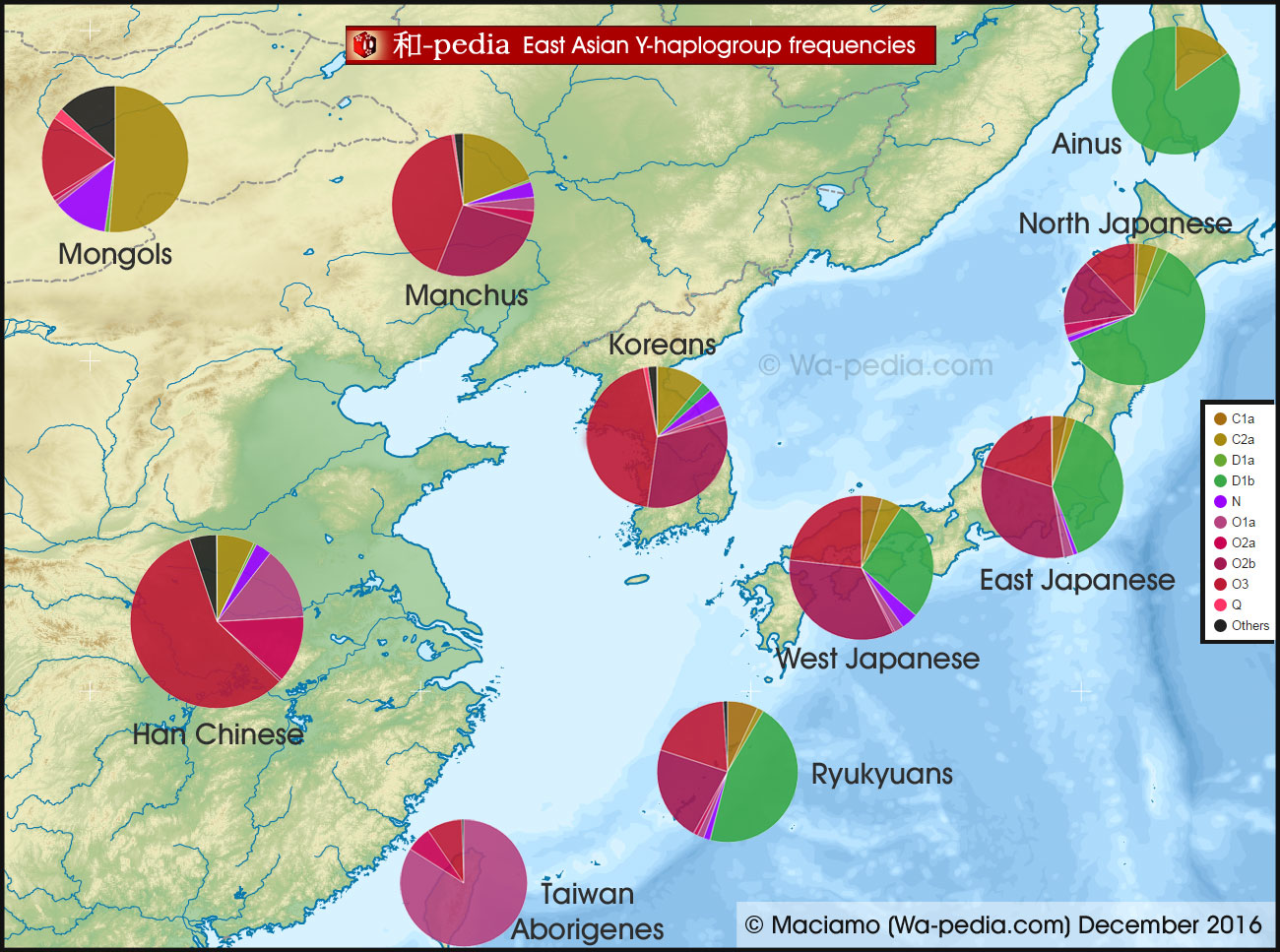

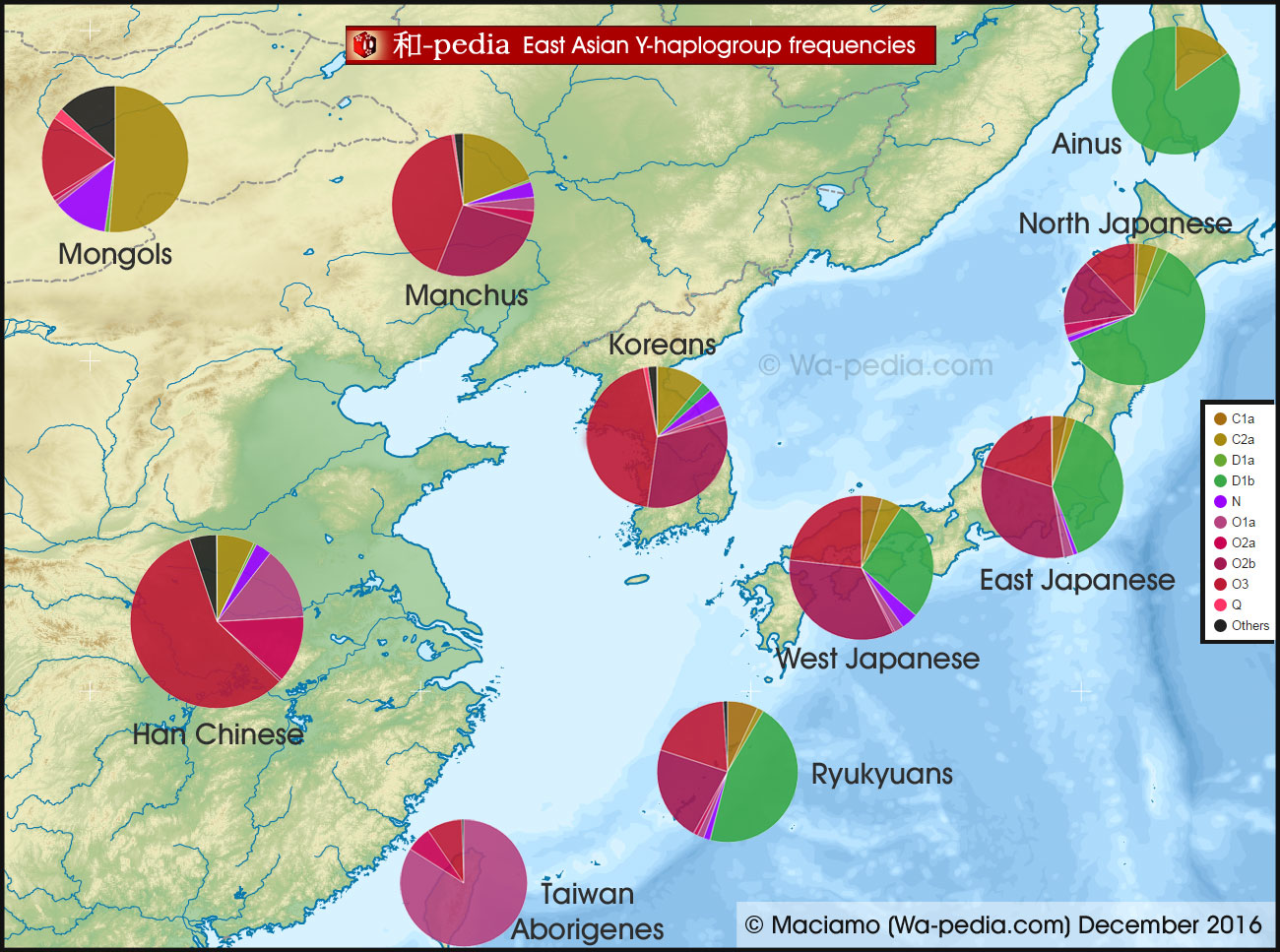

We clearly see, what the Japanese have what other typical East Eurasian lack is the Haplogroup D, that they most likely absorbed from Ainus and related groups. The three most typical parts for Japanese are the Ainu D, the Taiwanese O1a and the Han Chinese typical O2a.

I was expecting more Q1 among Mongols but it seems C2a is the stronger among them followed by O2.

Maybe the colours of the O subclades are not clear enough on the map, but the Chinese Neolithic O3 (red) is actually the dominant form of O among the Mongols, Manchus and Koreans, and the 2nd O subclade in Japan after O2b (dark violet). O2a (pink) is rare everywhere except in China and Southeast Asia. O1 (light violet) is found especially in Taiwan, southern China and Southeast Asia. You can see the exact percentages on the

Y-DNA table for East Asia.

As for D1b (former D2), the Ainus happen to have a lot of it, but that doesn't mean that the Japanese absorbed the Ainus. There were different tribes of hunter-gatherers in Japan during the Jōmon period (15,000-300 BCE). The Ainus were probably just the northern ones. The Ryukyuans also have a lot of D1b, but mixed with C1a1 (as opposed to C2a for the Ainus), and are autosomally distinct from the Ainus. The Japanese ethnicity emerged after the Yayoi people from Korea invaded Jōmon Japan from 500 BCE and the two populations blend together.

I recently hypothesised that a third population was also part of the genetic admixture of modern Japanese. Archaeologists had known for a while that from c. 4500 BCE some Jōmon tribes practised arboriculture as well as occasional agriculture. Even though it wasn't their main staple, the diversity of the crops cultivated can only be explained by the migration of Neolithic farmers from China. The crops included barley, barnyard millet, buckwheat, rice, bean, soybean, burdock, hemp, egoma and shiso mint, mountain potato, taro potato, and bottle gourd. Most of these domesticated plants, including rice and millet, are very unlikely to have been domesticated independently by the Jōmon hunter-gatherers.

A very little publicised study by Kenichi Shinoda (2003) identified Chinese-looking mtDNA lineages (haplogroups A, B, F, M8a and M10) in the Kanto region dating from the late Jōmon period mixed with typical Jōmon lineages (M7a, N9b). These Chinese lineages made up about 65 to 75% of the maternal lineages among the tested samples, which is huge, and was probably a local phenomenon limited to the few large fertile plains in Japan, while the rest of the mountainous country was surely inhabited primarily by hunter-gatherers. Nevertheless this is strong evidence that a migration from the continent took place long before the Yayoi invasion.

I have analysed in detail the mtDNA and Y-DNA of the Japanese and their neighbours and it struck me that some lineages looked much more South Chinese than Korean. That is the case of Y-haplogroups D1a1, O1a, O2a, O3a1, O3a2 and mt-haplogroups M7b, M7c, M9, M12. All of them are more common in southern China, Taiwan, Okinawa and Japan than in Korea. This, I believe, is another credible sign of a Neolithic colonisation of Japan from southern China, via Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa). I have also listed convincing

linguistic evidence that modern Japanese contains words and grammatical structure from Proto-Austronesian, the language of the South Chinese Neolithic farmers that colonised Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and in my opinion also Japan. Many linguists had argued before that Old Japanese was a mix of Korean/Altaic and Austronesian languages and had proposed that Jomon people spoke an Austronesian language. All the pieces of the puzzle seem to be falling into place now when combining archaeological and linguistic evidence with genetic one.