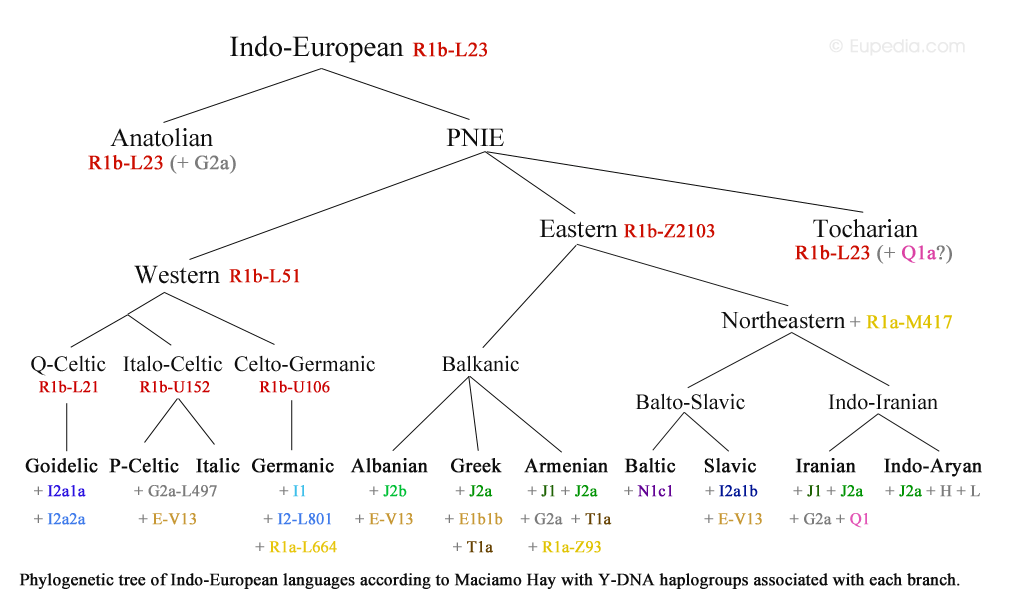

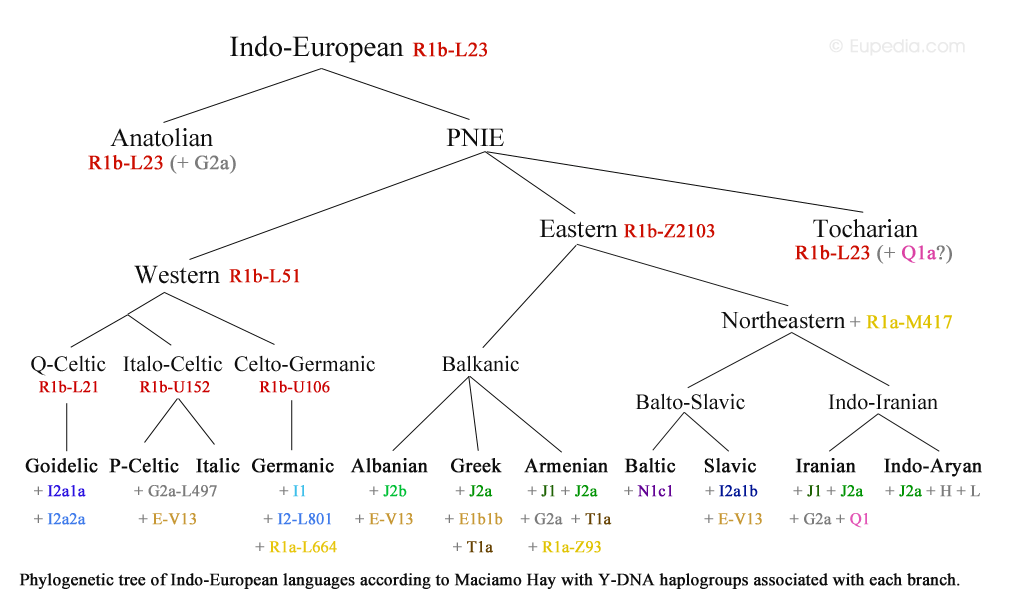

Johane Derite posted a list of different phylogenetic trees of IE languages proposed by various linguists in another thread. I thought it would be an ideal opportunity for me to post my proposed phylogenetic tree, which I have not only based on linguistic evidence, but also on archaeological and especially genetic evidence (using Y-chromosomal phylogeny). It differs radically from all the trees proposed by professional linguists, but mine is the only one that makes sense based on Y-DNA phylogeny and the known patterns of migrations combining archaeology and ancient DNA.

I have kept it simple and schematic, but I felt it was necessary to add the associated haplogroups to show that language evolve through population hybridisation, which tends to affect pronunciation and involves the absorption of loan words.

I believe that the Italo-Celtic branch intermingled more extensively with Neolithic European farmers than the Goidelic branch. This is obvious from the relatively high percentages of G2a-L497 and E-V13 among Hallstatt-derived Celts and Italics. I believe that this EEF mixture came originally from the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, although indirectly. The R1b-L51 branch expanded along the Danube to Central Europe while the R1a/R1b-Z2103 branch of the Corded Ware spread along the North European Plain. The latter would probably have been the ones who mixed with the scattered and by now nomadic tribes who abandoned the Trypillian cities in Western Ukraine. Corded Ware tribes met R1b-L51 tribes in Germany, Czechia and western Poland. But by that time some R1b-L21 and R1b-DF27 adventurers had already permeated the Bell Beaker trade network all the way to the Atlantic coast, before they got the chance to mix with Corded Ware people - hence the absence of E-V13 and G2a-L497 from these Atlantic Celts (Q-Celtic speakers). The Neolithic influence on language eventually led to the Q to P shift in Hallstatt and La Tène Celtic tongues, soon after the split with the Italic tribes.

Proto-Germanic R1b-U106 also mixed with the Corded Ware people and with the earlier inhabitants of the Netherlands, northern Germany and Denmark, who were probably heavier on Mesolithic ancestry and would have carried haplogroups I1 and I2-L801. I believe that a small but noteworthy non-IE pre-Germanic substratum exists in Germanic languages, although many linguists seem to be confused by the fact that some of these loan words eventually found their way in other IE languages because of the Germanic migrations. Germanic loan words infiltrated not only Romance, but also Slavic, Baltic, Albanian and possibly also Greek languages. Germanic languages also seem to have some Balto-Slavic influence, perhaps by the absorption of predominantly R1a Corded Ware tribes.

The complicated part that really get most linguists confused is the Eastern branch. This is because it is in fact two branches: the original East Yamna (R1b-Z2103) and the extension of that Yamna branch into the forest-steppe, which in my opinion is when the satem shift took place. The southern tribes of the Late Yamna and Catacomb (2800–2200 BCE) cultures (both R1b-Z2103) were ousted from the Pontic Steppe by the expansion of the Srubna culture (R1a with some R1b-Z2103) to the north, and the R1b-Z2103 migrated to the Balkans, where they became the Illyrians (incl. Proto-Albanian), Mycenaean Greeks, Phrygians and Proto-Armenians. The latter two eventually migrated from the Balkans to Anatolia around the time of the Bronze Age collapse c. 1200 BCE. Later influence from Iranian tribes in Armenia caused a partial satemisation of Armenian language. The same thing might have happened for Albanian and Greek due to the migrations of other Iranian tribes (Bulgars) and Slavs to the region. This is why Albanian and Armenian in particular cannot be definitely classified as centum or satem.

The Tocharian branch is in all likelihood descended from the Afanasievo culture (3300-2500 BCE), a Steppe culture in the Altai region that is contemporary to Yamna (3500-2500 BCE), but started a few centuries later.

I have wracked my brain about the Anatolian branch, bu IMO the most likely explanation remains that it was an early offshoot from the Pontic Steppe to the Balkans dating from 4200 to 3700 BCE. These people would have stayed a while in the Balkans then, like the Phrygians and Armenians much later, would have moved east to Anatolia. The oldest archaeological site associated with Anatolian IE speakers might be Troy, a city that was founded c. 3000 BCE to control the trade between the Aegean and the Black Sea region, including the Pontic Steppe. It makes sense that Steppe people should have wanted to control trade with their homeland. The language likely to have been prevalent in the historical city of Troy is Luwian, an Anatolian IE language.

I have kept it simple and schematic, but I felt it was necessary to add the associated haplogroups to show that language evolve through population hybridisation, which tends to affect pronunciation and involves the absorption of loan words.

I believe that the Italo-Celtic branch intermingled more extensively with Neolithic European farmers than the Goidelic branch. This is obvious from the relatively high percentages of G2a-L497 and E-V13 among Hallstatt-derived Celts and Italics. I believe that this EEF mixture came originally from the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, although indirectly. The R1b-L51 branch expanded along the Danube to Central Europe while the R1a/R1b-Z2103 branch of the Corded Ware spread along the North European Plain. The latter would probably have been the ones who mixed with the scattered and by now nomadic tribes who abandoned the Trypillian cities in Western Ukraine. Corded Ware tribes met R1b-L51 tribes in Germany, Czechia and western Poland. But by that time some R1b-L21 and R1b-DF27 adventurers had already permeated the Bell Beaker trade network all the way to the Atlantic coast, before they got the chance to mix with Corded Ware people - hence the absence of E-V13 and G2a-L497 from these Atlantic Celts (Q-Celtic speakers). The Neolithic influence on language eventually led to the Q to P shift in Hallstatt and La Tène Celtic tongues, soon after the split with the Italic tribes.

Proto-Germanic R1b-U106 also mixed with the Corded Ware people and with the earlier inhabitants of the Netherlands, northern Germany and Denmark, who were probably heavier on Mesolithic ancestry and would have carried haplogroups I1 and I2-L801. I believe that a small but noteworthy non-IE pre-Germanic substratum exists in Germanic languages, although many linguists seem to be confused by the fact that some of these loan words eventually found their way in other IE languages because of the Germanic migrations. Germanic loan words infiltrated not only Romance, but also Slavic, Baltic, Albanian and possibly also Greek languages. Germanic languages also seem to have some Balto-Slavic influence, perhaps by the absorption of predominantly R1a Corded Ware tribes.

The complicated part that really get most linguists confused is the Eastern branch. This is because it is in fact two branches: the original East Yamna (R1b-Z2103) and the extension of that Yamna branch into the forest-steppe, which in my opinion is when the satem shift took place. The southern tribes of the Late Yamna and Catacomb (2800–2200 BCE) cultures (both R1b-Z2103) were ousted from the Pontic Steppe by the expansion of the Srubna culture (R1a with some R1b-Z2103) to the north, and the R1b-Z2103 migrated to the Balkans, where they became the Illyrians (incl. Proto-Albanian), Mycenaean Greeks, Phrygians and Proto-Armenians. The latter two eventually migrated from the Balkans to Anatolia around the time of the Bronze Age collapse c. 1200 BCE. Later influence from Iranian tribes in Armenia caused a partial satemisation of Armenian language. The same thing might have happened for Albanian and Greek due to the migrations of other Iranian tribes (Bulgars) and Slavs to the region. This is why Albanian and Armenian in particular cannot be definitely classified as centum or satem.

The Tocharian branch is in all likelihood descended from the Afanasievo culture (3300-2500 BCE), a Steppe culture in the Altai region that is contemporary to Yamna (3500-2500 BCE), but started a few centuries later.

I have wracked my brain about the Anatolian branch, bu IMO the most likely explanation remains that it was an early offshoot from the Pontic Steppe to the Balkans dating from 4200 to 3700 BCE. These people would have stayed a while in the Balkans then, like the Phrygians and Armenians much later, would have moved east to Anatolia. The oldest archaeological site associated with Anatolian IE speakers might be Troy, a city that was founded c. 3000 BCE to control the trade between the Aegean and the Black Sea region, including the Pontic Steppe. It makes sense that Steppe people should have wanted to control trade with their homeland. The language likely to have been prevalent in the historical city of Troy is Luwian, an Anatolian IE language.