Introduction

The human body hosts hundreds of billions of bacteria, a number that varies with the food we eat, how often we wash ourselves, brush our teeth, take antibiotics or drink alcohol or other antibacterials (ginger, garlic, turmeric), but generally exceeds the number of human cells, and can even occasionally outnumber them by a factor of ten to one. These bacteria live in symbiosis with us, helping us digesting foods, metabolizing vitamins, sugars, fats and amino acids, enhancing our immune system, and protecting us from other pathogenic bacteria or fungi. Together with viruses and fungi that reside inside us they form our microbiome. Disruption of the delicate balance of our microbiota can lead to a whole range of health problems, such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, colitis, cancer, bacterial vaginosis, strep throat, ear infection, nose congestion, eczema, chronic fatigue syndrome, and more. This phenomenon is known as dysbiosis.

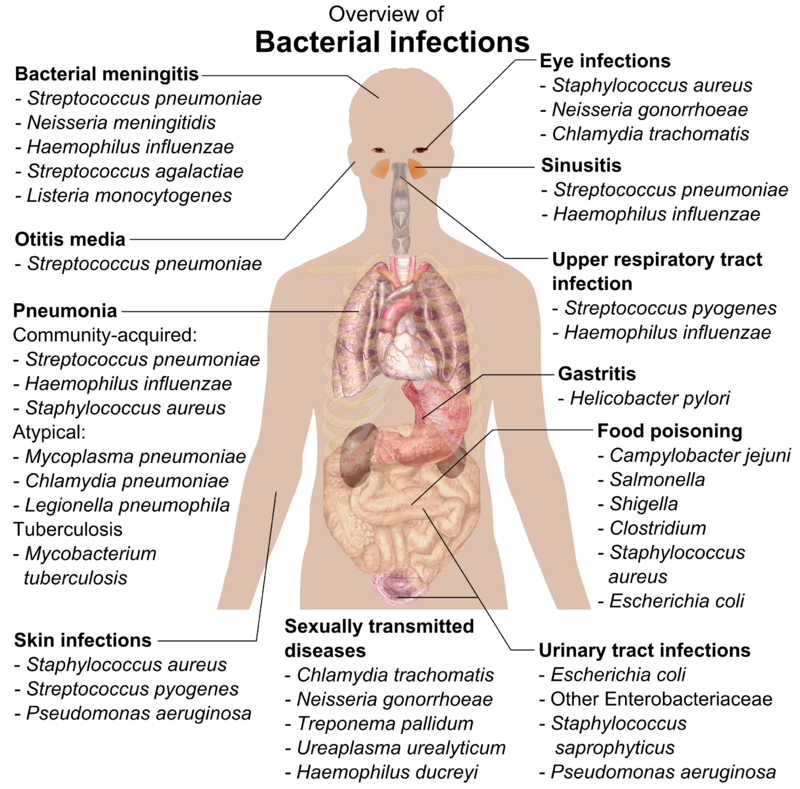

t is a common misconception that bacteria live inside our body. Technically, they live on us, on our skin and in mucosal cavities that pass through our body, like the respiratory and digestive tracts, but they should never penetrate within the blood, joints, bones or organs. Any bacteria is potentially pathogenic if it enters the bloodstream or set up residence within our organs. When this happens, however, our immune system reacts immediately and gets rid of the invaders. The term pathogenic bacteria is used for species that are so aggressive that they to kill commensal bacteria, leading to dysbiosis (e.g. diarrhea), or manage to defeat or thwart or white blood cells, causing inflammation and tissue damage (think pneumonia, sinusitis, otitis, meningitis and the like).

Most, if not all, autoimmune diseases are also caused by bacteria (or more rarely fungi) that manage to infiltrate the body and that the immune system cannot get rid of, either because we are too weak (immunocompromised, overly tired, fighting too many infections at once), or our immune system (HLA system) cannot recognize and appropriately fight one type of pathogen, or because damage to the gut lining (known as Leaky Gut Syndrome) caused by environmental toxins, food intolerances, excess alcohol, antibiotics and the like, allow bacteria to penetrate in the body.

Once they are inside, they will set up colonies in areas difficult to reach by the immune system (i.e. with low blood flow) like the joints, causing autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. The latter is caused by the Klebsiella bacteria and typically invades host who possess the HLA-B27 type. Other bacteria might infect the pancreas, causing Type I diabetes, or the muscle fibre, causing fibromyalgia, or directly attacking nerves, which first causes peripheral neuropathies then can lead to Multiple sclerosis (MS). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is often caused by infections of extremely tiny and primitive bacteria that lack a cell wall known as Mycoplasma, or other unusual bacteria like Borrelia (the cause of Lyme Disease). It has been reported (by Dr Schoemaker) that some types of HLA-DR types cannot easily get rid of Borrelia (DR15, DR16), Dinoflagellates (DR4) and other types of bacteria.

Additionally, bacteria (and fungi) can form a biofilm around them, a sort of slime that protects them from the immune system. If a body part is infected by a bacterial colony protected by a biofilm it will cause a chronic disease that can last for years or even for one's life time. New medicine are being developed to dissolve biofilms, and some natural supplements like serrapeptase could achieve just that.

The interaction between the immune system and our microbiota is what keeps us healthy and makes us sick. That is possible the single most important thing to know about one's health, and yet until recently it was impossible to know what bacteria lived on our bodies. Most people don't know their HLA types (even doctors) even though they are far more useful than blood types or commonly prescribed tests like cholesterol levels. 23andMe uses HLA types to determine risks for dozens of medical conditions, from psoriasis to Type I diabetes.

At present I only known of two companies that test the microbiome: the American Gut Project, available only in the U.S. and testing only the gut microbiome, and Ubiome, available worldwide and testing any site your want (gut, mouth, nose, ear, skin, genitals...). Here is how to understand your gut results.

Gut microbiome: what does it all mean ?

First, the basics. There are five main phyla of bacteria found in the human digestive tract:

- Firmicutes : The most common phylum in most Westerners. It includes both beneficial digestive bacteria (Anaerostipes, Blautia, Dorea, Flavonifractor, Lactobacillus, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Robeburia, Ruminococcus, Sarcina, etc.) and pathogenic ones (Listeria, Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile). Depending on their class, they can be either Gram-positive or Gram-negative.

- Bacteroidetes : The second most common phylum among Westerners, but the most common in some non-Western countries. Bacteroidetes are Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria that can help us digest vegetables (Prevotella), digest fats (Alistipes), digest whole grains and ferment glucose (Bacteroides), or help us regulate our immune system (Barnesiella). Most other Bacteroidetes, however, are pathogenic and shouldn't be found in a healthy microbiome. For example, Porphyromonas have been linked to rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease and bacterial vaginosis.

- Verrucomicrobia : Tiny wart-shaped bacteria usually found in fresh water and soil. The most common species found in the human gut is Akkermansia, which degrades the excess mucin (mucosal slime) produced by the gut lining. Akkermansia is anti-inflammatory and protective against obesity, colon cancer and autism.

- Proteobacteria : These Gram-negative bacteria are essentially bad and include lots of dreaded pathogens like : Bordetella (pertussis), Brucella (brucellosis), Campylobacter (gastroenteritis), Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori (gastritis and gastric ulcers), Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio (e.g. V. cholerae, the causative agent of cholera), and Yersinia (e.g. Y. pestis, the causative agent of the plague). The varieties most commonly found in the gut are Enterobacter (opportunistic infections), Haemophilus (common in the mouth and nose, but can cause respiratory tract infections), Desulfovibrio (linked to IBS and autism), Kluyvera, Sutterella (linked to autism) and Thalassospira.

- Actinobacteria : Some of the most common microbes found in our mouths and genitals. They are Gram-positive and typically play a role in decomposing organic matter. The varieties found in the gut are usually beneficial like Collinsella, Cryptobacterium curtum and Bifidobacterium (which is even used as a probiotics and added to Activia yoghurt).

Next, what proportion of good bacteria do you want in your gut ?

Brown et al. (2011) explained how butyrate-producing bacteria protects your gut from inflammation, ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. Six main families of firmicutes are known for their ability to convert lactic acid into butyric acid (butyrate). These are Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, Faecalibacterium, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Roseburia and Subdoligranulum. Butyric acid induces mucin synthesis and tightens the junctions between epithelial cells, thus preventing inflammation and leaky gut syndrome.

Nevertheless, Bacteoridetes like Bacteroides and Alistipes will convert lactic acid into other short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetic acid, formic acid or propionic acid, which, if present in too large quantities, will damage the lining of the gut, causing inflammation and hyperpermeability of the intestines, leading to autoimmune diseases. So, although Bacteroides and Alistipes are useful and beneficial to digest whole grains and fats, if their proportion exceeds that of the butyrate-producing firmicutes above, it will most probably cause illness. It is therefore important to keep a higher ratio of butyrate-producing bacteria - if possible two or three times more than the Bacteroides and Alistipes. But you also don't want to have too few Bacteroides and Alistipes, as they can also protect you against pathogenic bacteria.

Lactic acid is produced by the lactic bacteria found in yoghurt and probiotics like lactobacillus and bifidobacterium.

Here is the chart summarising the two pathways (from Brown et al. 2011).

The human body hosts hundreds of billions of bacteria, a number that varies with the food we eat, how often we wash ourselves, brush our teeth, take antibiotics or drink alcohol or other antibacterials (ginger, garlic, turmeric), but generally exceeds the number of human cells, and can even occasionally outnumber them by a factor of ten to one. These bacteria live in symbiosis with us, helping us digesting foods, metabolizing vitamins, sugars, fats and amino acids, enhancing our immune system, and protecting us from other pathogenic bacteria or fungi. Together with viruses and fungi that reside inside us they form our microbiome. Disruption of the delicate balance of our microbiota can lead to a whole range of health problems, such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, colitis, cancer, bacterial vaginosis, strep throat, ear infection, nose congestion, eczema, chronic fatigue syndrome, and more. This phenomenon is known as dysbiosis.

t is a common misconception that bacteria live inside our body. Technically, they live on us, on our skin and in mucosal cavities that pass through our body, like the respiratory and digestive tracts, but they should never penetrate within the blood, joints, bones or organs. Any bacteria is potentially pathogenic if it enters the bloodstream or set up residence within our organs. When this happens, however, our immune system reacts immediately and gets rid of the invaders. The term pathogenic bacteria is used for species that are so aggressive that they to kill commensal bacteria, leading to dysbiosis (e.g. diarrhea), or manage to defeat or thwart or white blood cells, causing inflammation and tissue damage (think pneumonia, sinusitis, otitis, meningitis and the like).

Most, if not all, autoimmune diseases are also caused by bacteria (or more rarely fungi) that manage to infiltrate the body and that the immune system cannot get rid of, either because we are too weak (immunocompromised, overly tired, fighting too many infections at once), or our immune system (HLA system) cannot recognize and appropriately fight one type of pathogen, or because damage to the gut lining (known as Leaky Gut Syndrome) caused by environmental toxins, food intolerances, excess alcohol, antibiotics and the like, allow bacteria to penetrate in the body.

Once they are inside, they will set up colonies in areas difficult to reach by the immune system (i.e. with low blood flow) like the joints, causing autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. The latter is caused by the Klebsiella bacteria and typically invades host who possess the HLA-B27 type. Other bacteria might infect the pancreas, causing Type I diabetes, or the muscle fibre, causing fibromyalgia, or directly attacking nerves, which first causes peripheral neuropathies then can lead to Multiple sclerosis (MS). Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is often caused by infections of extremely tiny and primitive bacteria that lack a cell wall known as Mycoplasma, or other unusual bacteria like Borrelia (the cause of Lyme Disease). It has been reported (by Dr Schoemaker) that some types of HLA-DR types cannot easily get rid of Borrelia (DR15, DR16), Dinoflagellates (DR4) and other types of bacteria.

Additionally, bacteria (and fungi) can form a biofilm around them, a sort of slime that protects them from the immune system. If a body part is infected by a bacterial colony protected by a biofilm it will cause a chronic disease that can last for years or even for one's life time. New medicine are being developed to dissolve biofilms, and some natural supplements like serrapeptase could achieve just that.

The interaction between the immune system and our microbiota is what keeps us healthy and makes us sick. That is possible the single most important thing to know about one's health, and yet until recently it was impossible to know what bacteria lived on our bodies. Most people don't know their HLA types (even doctors) even though they are far more useful than blood types or commonly prescribed tests like cholesterol levels. 23andMe uses HLA types to determine risks for dozens of medical conditions, from psoriasis to Type I diabetes.

At present I only known of two companies that test the microbiome: the American Gut Project, available only in the U.S. and testing only the gut microbiome, and Ubiome, available worldwide and testing any site your want (gut, mouth, nose, ear, skin, genitals...). Here is how to understand your gut results.

Gut microbiome: what does it all mean ?

First, the basics. There are five main phyla of bacteria found in the human digestive tract:

- Firmicutes : The most common phylum in most Westerners. It includes both beneficial digestive bacteria (Anaerostipes, Blautia, Dorea, Flavonifractor, Lactobacillus, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Robeburia, Ruminococcus, Sarcina, etc.) and pathogenic ones (Listeria, Staphylococcus, Clostridium difficile). Depending on their class, they can be either Gram-positive or Gram-negative.

- Bacteroidetes : The second most common phylum among Westerners, but the most common in some non-Western countries. Bacteroidetes are Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria that can help us digest vegetables (Prevotella), digest fats (Alistipes), digest whole grains and ferment glucose (Bacteroides), or help us regulate our immune system (Barnesiella). Most other Bacteroidetes, however, are pathogenic and shouldn't be found in a healthy microbiome. For example, Porphyromonas have been linked to rheumatoid arthritis, periodontal disease and bacterial vaginosis.

- Verrucomicrobia : Tiny wart-shaped bacteria usually found in fresh water and soil. The most common species found in the human gut is Akkermansia, which degrades the excess mucin (mucosal slime) produced by the gut lining. Akkermansia is anti-inflammatory and protective against obesity, colon cancer and autism.

- Proteobacteria : These Gram-negative bacteria are essentially bad and include lots of dreaded pathogens like : Bordetella (pertussis), Brucella (brucellosis), Campylobacter (gastroenteritis), Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori (gastritis and gastric ulcers), Salmonella, Shigella, Vibrio (e.g. V. cholerae, the causative agent of cholera), and Yersinia (e.g. Y. pestis, the causative agent of the plague). The varieties most commonly found in the gut are Enterobacter (opportunistic infections), Haemophilus (common in the mouth and nose, but can cause respiratory tract infections), Desulfovibrio (linked to IBS and autism), Kluyvera, Sutterella (linked to autism) and Thalassospira.

- Actinobacteria : Some of the most common microbes found in our mouths and genitals. They are Gram-positive and typically play a role in decomposing organic matter. The varieties found in the gut are usually beneficial like Collinsella, Cryptobacterium curtum and Bifidobacterium (which is even used as a probiotics and added to Activia yoghurt).

Next, what proportion of good bacteria do you want in your gut ?

Brown et al. (2011) explained how butyrate-producing bacteria protects your gut from inflammation, ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. Six main families of firmicutes are known for their ability to convert lactic acid into butyric acid (butyrate). These are Anaerostipes, Flavonifractor, Faecalibacterium, Pseudobutyrivibrio, Roseburia and Subdoligranulum. Butyric acid induces mucin synthesis and tightens the junctions between epithelial cells, thus preventing inflammation and leaky gut syndrome.

Nevertheless, Bacteoridetes like Bacteroides and Alistipes will convert lactic acid into other short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetic acid, formic acid or propionic acid, which, if present in too large quantities, will damage the lining of the gut, causing inflammation and hyperpermeability of the intestines, leading to autoimmune diseases. So, although Bacteroides and Alistipes are useful and beneficial to digest whole grains and fats, if their proportion exceeds that of the butyrate-producing firmicutes above, it will most probably cause illness. It is therefore important to keep a higher ratio of butyrate-producing bacteria - if possible two or three times more than the Bacteroides and Alistipes. But you also don't want to have too few Bacteroides and Alistipes, as they can also protect you against pathogenic bacteria.

Lactic acid is produced by the lactic bacteria found in yoghurt and probiotics like lactobacillus and bifidobacterium.

Here is the chart summarising the two pathways (from Brown et al. 2011).

Last edited: