The Roman Empire was founded by Julius Caesar's heir, Caesar Augustus. Not only was Augustus the man who laid the foundations of the empire, but also the longest serving emperor, and in the eyes of many, the best ruler Rome ever had. And even though Augustus has become one of the most famous people in world history and is still much celebrated 2000 years after his death, few people think of his right-arm, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (63-12 BCE), who was is de facto co-emperor for 15 years, from 27 BCE to his death in 12 BCE. Agrippa's children were adopted by Augustus as his heirs. They died before Augustus, but Agrippa's bloodline nevertheless passed to two ruling emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (Caligula and Nero).

In the words of Lindsay Powell in his biography Marcus Agrippa: Right-hand Man of Caesar Augustus: "Agrippa was a remarkable and multifaceted man who complemented his friend in age, outlook, personality and skills. He was a talented general on land and a fine admiral at sea, a pragmatic diplomat, a hard working public official, a generous philanthropist and the loyalest of friends. He was Augustus’ ‘go-to guy’, the man the boss turned to whenever he needed a difficult job done, whether it was beating tough guerillas in northern Spain or fixing creaking sewers in Rome. There were many times when he could have challenged Augustus and usurped power for himself, yet he did not."

The greatest military commander of his time

Unlike his great-uncle Julius Caesar, Octavian was never a very able general. Times and again his key military victories were owed to Marcus Agrippa. In 42 BCE, two years after Mark Antony and Octavian defeated the anti-Caesarians led by Bruttus and Cassius at Philippi, Sextus Pompey, the younger son of Pompey the Great, seized Sicily and Sardinia for the Republican faction opposed to the triumvirs. In doing so he prevented grain from these islands and from North Africa to reach Rome, effectively setting up a naval blockade of the Italian Peninsula. After a brief peace treaty signed in 39 BCE, Octavian attempted to recover Sicily but was defeated in the naval battle of Messina in 37 BCE. Octavian now turned to his friend's help. Agrippa started by creating a safe naval base near Naples by linking Lake Avernus to the sea, thus creating Portus Julius. He then spent winter training a navy on land and building a fleet. Agrippa fought Sextus at Mylae in August 36 BCE, and again a month later, while Lepidus and Statilius Taurus invaded Sicily. In the Battle of Naulochus Agrippa destroyed Sextus' fleet, losing only 3 of his 300 ships against 28 sunk ships and over 260 ships caputred on the Pompeian side. Following the battle, Octavian dismissed Lepidus as a triumvir and became the sole ruler of the western half of Roman territories.

After years of sharing power, time had come in 31 BCE for the last two triumvirs, Octavian and Mark Antony, to face each others for the domination of Roman world. The confrontation took place on the coast of western Greece in what is known as the Battle of Actium. This other momentous naval battle was once again won mostly by Marcus Agrippa's superior skills. In doing so Agrippa defeated Mark Antony, who had been Julius Caesar's most able general and was widely regarded as the most able Roman military commander after Caesar's death. Now that honour went to Agrippa, and he would never be defeated. Actium was the last battle of the Roman Republic. The victory allowed Octavian to become sole ruler of Rome and to establish the Roman Empire.

Anthony Everitt summarises Agrippa's invaluable role by Octavian's side: "Straightforward, direct and loyal, he was the finest general and admiral of the age. He made up for Octavian's lack of military skills, as had been tacitly acknowledged by the award of the corona rostrata for his services in the Naulochus campaign. The war against Sextus Pompeius would not have been won without him, and he had been discreetly invaluable in Illyricum. Now, as the mastermind of victory at Actium, he received the right to display azure banner and (of more practical value) the freehold of country estates in Egypt." [2]

Agrippa the statesman

Agrippa didn't just do Augustus's bidding and he was much more than an excellent general and admiral. He served three times as consul (in 37, 28 and 27 BCE) - as many times as Pompey the Great, and already an achievement in itself.

As Lindsay Powell explains: "Where Agrippa brought tried and tested know-how in management and military science, Maecenas provided the connections and panache Imperator Caesar needed to get things done in political Rome. To speak and act for him in his absence, Caesar empowered both men: He also gave to Agrippa and to Maecenas so great authority in all matters that they might even read beforehand the letters which he wrote to the Senate and to others and then change whatever they wished in them. To this end they also received from him a ring, so that they might be able to seal the letters again. For he had caused to be made in duplicate the seal which he used most at that time, the design being a sphinx, the same on each copy; since it was not till later that he had his own likeness engraved upon his seal and sealed everything with that then."

"Of the twenty-four fasces given to Caesar as consul up to 29 BCE, Agrippa now received half of them, demonstrating publicly that he considered the two consuls were of equal status. Furthermore he provided Agrippa with a tent similar in size and design to his own so that when they were campaigning together they would be seen as equal, and the watchword was to be given out by both of them from that time on." [1]

In 28 BCE, Augustus Caesar assumed the office of Censor with Agrippa as his colleague. The office was the most prestigious in the Roman Republic. It was open only to former consuls, and unlike them censors were not elected for only one year but normally for five years. The power of the censors was absolute. No magistrate could oppose their decisions, and only another censor who succeeded them could cancel it. Their duties included upholding public morals, administering the state's finances, overseeing public works, and of course taking the census of Roman citizens and of their property. Censors had the right, among others, to exclude a man from the ranks of senators. The office was abolished after 22 BCE.

In 23 BCE, Agrippa was granted imperium proconsulare for an additional 10 years, meaning that he would enjoy the same authority as a consul for a whole decade - more than anyone else in Roman Republican history, surpassing Gaius Marius, Cornelius Sulla and Julius Caesar.

In 21 BCE, Augustus married his only child, Julia, to Agrippa. In the words of Lindsay Powell: "By marrying his only child to his best friend, Augustus was now clearly communicating his intention of making Agrippa co-ruler of the Roman world. There was no other way to interpret it." [1] Five children were born from this union, including two sons, Gaius and Lucius, whom Augustus would adopt as his heirs.

In 18 BCE, Augustus and Agrippa both received tribunician power for 5 years (18-13 BCE), meaning that their persons were now sacrosanct like that of an elected Tribune of the Plebs, without actually serving as such (the office had been abolished in 27 BCE). The only person who had being conferred such an honour before was Julius Caesar.

Finally, in 13 BCE Agrippa obtained imperium proconsulare maius (supreme power even over sitting consuls), which is to say the exact same imperial power as Augustus across the entire Roman world. This status was higher than dictator and would become a hallmark of the Roman emperor. Unfortunately Agrippa died from a mysterious disease after his return from campaign in Illyria the next year.

During their joint rule, coins were minted either showing the ephigy of Augustus or Agrippa. Some represented the two rulers together, like this famous Dupondius of Nemausus (Nîmes).

Lindsay Powell says that "When Herodes returned to his capital at Hierosolyma (Jerusalem), he called the two most opulent rooms in the new palace he was building respectively Caesareum and Agrippeum, after the eminent Romans." [1]

From the time of the Tetrarchy (284-324 CE) onwards, each Roman emperor was assissted by a junior emperor. They used the title of Augustus for the senior emperor and Caesar for the junior emperor, who was also his designated heir. Augustus trusted Agrippa so much that Agrippa was basically in charge of everything in Rome when Augustus was away - just like a Caesar to his Augustus in the Late Roman Empire. It is also clear that Augustus wanted Agrippa to be seen as his equal in many regards, not just a junior emperor.

Many Roman emperors had a notoriously short life expectancy after taking up the purple. Galba was only emperor for 3 weeks, and in total 18 emperors ruled for less than 1 year in the three centuries between the rules of Augustus and Constantine. In contrast Marcus Agrippa was Rome's second most important man for 19 years (from 31 BCE to his death in 12 BCE), as long as the reigns of Trajan or Marcus Aurelius. In fact only four emperors ruled longer, including Augustus (the other three are Tiberius, Antonius Pius and Hadrian).

Agrippa the builder

Augustus famously quipped on his deathbed that he had found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble. But the truth is that Agrippa was the man who transformed the face of the city and of major Roman colonies, of his own initiative. We owe to Marcus Agrippa:

- The Aqua Virgo (one of the main aqueducts in Rome, which still works today and feed many of Rome's fountains, including the Trevi Fountain).

- The Aqua Julia, another of Rome's aqueducts.

- The Panthenon.

- The Thermae Agrippae, Rome's first public baths, which would be unrivalled in size and engineering until Trajan's Baths. See excerpt from the book below.

In addition, Agrippa renovated Rome's sewers, the Cloaca Maxima, for the first time since they were built many centuries before. He renovated the streets and public buildings of Rome like never before.

Outside of Rome, Agrippa built (among others):

- The Portus Iulius in Naples.

- The Maison Carrée in Nîmes (as well as the city walls and other buildings), which is the best known Roman temple in France today.

- The Via Agrippa, actually a network of 21,000 km of four Roman roads in Gaul leaving from Lyon (to Cologne, Boulogne-sur-Mer, Arles and Saintes).

- The Roman Theatre of Mérida in Spain, which is listed as a World Heritage site by the UNESCO.

- The Odeon of Agrippa in Athens, now lost.

- In Antioch he enlarged the theatre, rebuilt the stadium and constructed an entire residential area south of the stoa.

Agrippa founded the Colonia Ubiorum (modern Cologne), which would be renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium or simply Colonia Agrippinensis.

I will cite a few more passages from Lindsay Powell's book to illustrate just how important were Agrippa's achievements as an architect and urban planner.

"Agrippa was driven by a design ethos that public works for the benefit of the people must also look beautiful. Pliny the Elder wrote with admiration of how: He also formed 700 wells, in addition to 500 fountains, and 130 reservoirs, many of them magnificently adorned. Upon these works, too, he erected 300 statues of marble or bronze, and 400 marble columns – and all this in the space of a single year! Remarkable too was the fact that he completed these projects without any public funding. Financially, Agrippa was by now a very wealthy man in his own right and could afford the expense from proceeds of confiscations under the proscriptions and the estates in Sicily and Illyricum, but additional funds were probably provided by Caesar. Administratively, Agrippa’s unique systems approach to the provision, distribution and drainage of water set a new standard in city management."

"Where Augustus had used the last three years to reform Rome’s political structure, Agrippa would use the next three to transform the city itself."

"In the wake of the constitutional arrangement, choosing to rebuild the Saepta clearly demonstrated the régime’s full commitment to free elections within Rome’s republican democracy. Its official name, the Saepta Iulia, acknowledged Iulius Caesar’s original plans but, by dint of his family connection, it emphasized Augustus’ support of the institution for which it was built. It was a large rectangular enclosure, measuring 310m (1,017ft) long by 120m (393ft) wide, surrounded by a covered colonnade to protect voters from rain or rays of the sun. Rather than leaving its walls plain, Agrippa adorned the new structure with marble tablets and paintings to provide a pleasant space for voters to enjoy while they cast their ballots and to encourage people to visit and linger at other times of the year. Some of the finest, and costliest, sculptures decorated its interior space."

"Having spent several years away following the ‘First Constitutional Settlement’, during which Agrippa had been the sole face of the new régime in Rome, now that Augustus was in good health again it was time for him to reassert himself onto the political and social scene."

"Adjoining and expanding the original covered Spartan Baths erected in 25 BCE, a new complex of damp heat baths had been built (map 11). Called the Thermae Agrippae it was a marvel of hydraulic engineering. There had been bathing complexes in Rome before, but in scale and lavishness the Baths of Agrippa were the first of their kind and, for the next three centuries, future rulers of Rome would try to outdo them in size and luxury. The building, oriented north and south on the same axis as the Pantheon and Saepta Iulia, covered an area of approximately 100–120m (328–393ft) north and south and 80–100m (262–328ft) east and west.."

[...]

"Fitness enthusiasts could avail themselves of the colonnaded exercise yard outside. Keen swimmers could use the Euripus, a manmade canal fed directly by the Aqua Virgo – indeed, an estimated 20 per cent of the water it carried was just for this purpose – which extended right down to the Tiber.The first to try the fresh spring water as it filled the canal and bathing pools were struck by its coldness, clarity and purity. The soft, cool water was considered particularly fine to swim in and the poet Martial declared that it was so brilliantly clear that an observer could scarcely perceive it even was there, and only the polished marble surface over which it flowed, with barely a ripple, revealing it.Seneca used to mark the beginning of the New Year by taking a cold plunge in the Virgo, while Ovid hung around its porticoes to enjoy the views of the Campus Martius, and to find women."

"To the west of the bathing complex, Agrippa created an immense artificial lake, the Stagnum Agrippae, but about which little is known. Completing and uniting these leisure facilities, between Euripus and the artificial lake Agrippa created a great park called the Horti Agrippae. Eager to leave Rome’s crowded streets and cramped alleyways, people thronged the park’s gravel paths to enjoy the manicured lawns and careful plantings, managed fishponds and collections of artworks.Art mattered to Agrippa, and it was important to him that it could be enjoyed by all. He made an impassioned speech during his lifetime on the subject of public ownership of art, about which Pliny the Elder later wrote: we have a magnificent oration of his, and one well worthy of the greatest of our citizens, on the advantage of exhibiting in public all pictures and statues; a practice which would have been far preferable to sending them into banishment at our country-houses.Among the many items put on display in the new Gardens which bore his name, Agrippa dedicated statues he had purchased on his travels in Asia.The combined effect of the lavish development of temple, baths, canal, lake and park, which together transformed the unkempt Campus Martius into a manicured playground for the Roman people, was one of opulence and splendour. It was made all the more appealing for its accessibility to all classes of society with free admission." [1]

Agrippa the traveller

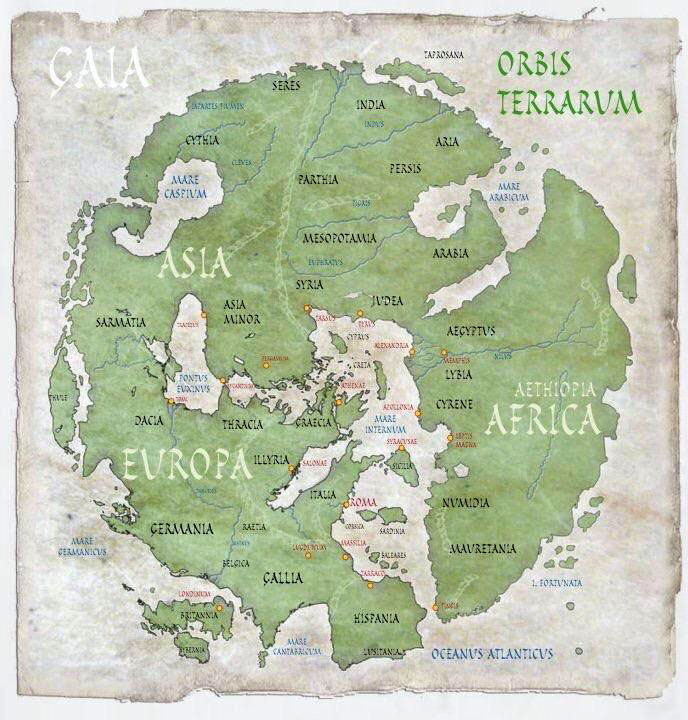

Agrippa worked for many years on making a great map of the world, known as the Dimensuratio provinciarum, or Orbis terrarum, which was inscribed in marble by Augustus and displayed in the Porticus Vipsania at Rome. It remained the reference map of the world throughout Roman and medieval times. Agrippa was one of the most travelled men of his time.

Conclusion

All in all, Marcus Agrippa achieved more in pretty much all regards, be it as military commander, politician, administrator or architect, than most Roman emperors ever did. In terms of overall achievements, I would without hesitation place him in the best rulers of the Roman Empire, alongside Augustus, Vespasian and Trajan. Other renowned emperors like Nerva, Antonius Pius and Marcus Aurelius were good people with admirable qualities, but they were not great generals, reformers, nor builders. Hadrian was great in many respects, but was arrogant and overly authocratic.

What I like about Agrippa, besides his amazing abilities, is his outstanding character. He always remained loyal and trustworthy toward Augustus. He was extremely generous, sponsored the construction of public buildings all around the empire and always thought of the public good. He earned the respect and good-will of the provincials, including and especially from the Jewish population - a fact rare enough with Roman rulers to be mentioned, as many 'good' emperors like Vespasian, Titus, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius had particularly strained relations (to say the least) with the Jews.

Despite his high status and his numerous victories, Agrippa always remained humble. The Senate granted him three triumphs, for his quelling of the rebellions in Aquitania (38 BCE), against the Asturians and Cantabrians (19 BCE), and for annexing the Crimea (17 BCE). Yet he always turned down the honour.

Sources

- Marcus Agrippa: Right-hand Man of Caesar Augustus, by Lindsay Powell

- Augustus: The Life of Rome's First Emperor, by Anthony Everitt

- Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World, by Adrian Goldsworthy

- The Emperors of Rome: The Story of Imperial Rome from Julius Caesar to the Last Emperor, by David Potter

- Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine, by Barry Strauss

- Lives of the Romans, by Philip Matyszak