The idea may have sounded ridiculous to many scientists not so long ago. After all, when are born our brain is supposedly a blank slate. DNA only constitutes the body's building blocks, and the principles of Darwinian evolution states that any new mutation arises fortuitously. In contrast, Lamarck believed that an organism could pass on characteristics that it acquired during its lifetime to its offspring. The famous example that Lamarck gave was that "if giraffes stretch their necks to reach high leaves, their offspring have longer necks."

Even though the Lamarckian model of evolution was discredited as soon as it was proposed by the French scientists in the 18th century, the concept may make a come back thanks to new discoveries in the field of epigenetics. Two months ago, Brian G Dias & Kerry J Ressler published a paper in the journal Nature, in which they explain that mice whose father or grandfather learned to associate the smell of cherry blossom with an electric shock became more nervous than mice in the control group when exposed to the same odour, even though they never received the electric shock themselves. You can read about it in more details here.

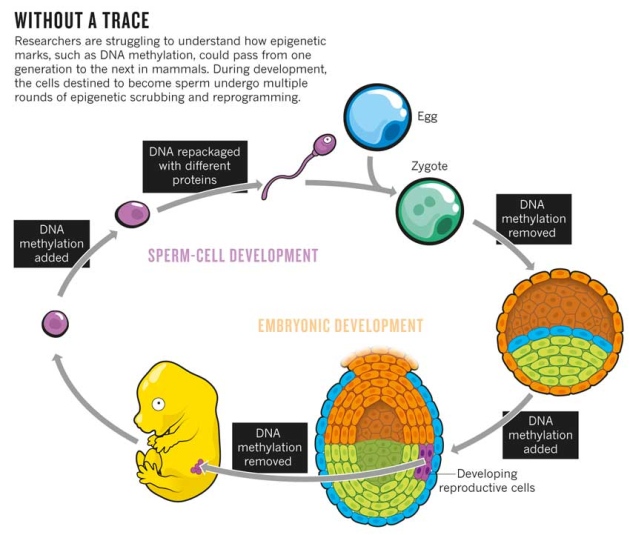

If the study can be replicated with other stimuli and other animal it would mean that acquired fears, and by extension also memories, behaviours or even abilities can be inherited. This can be explained by the activation or deactivation of some genes through the process of DNA methylation and histone modification, which are the basis of epigenetic inheritance. Genes can be made more 'reactive' or 'sensitive' to stimuli, or conversely 'silenced' during an individual's life, due to a repeated exposure or behaviour, or due to a traumatic event. These changes are henceforth inherited by later generations, although they will weaken at each new generation and return to 'normal' after a few generations if the stimuli that caused the methylation are not repeated by the offspring.

There are been many human cases of apparently inherited fears or trauma, running in families for several generations, that were left unexplained by science. This could be for instance an irrational fear for the noise made by air raid sirens among children of young individuals (who hadn't had children yet) who experienced traumatic fears during air raids in WWII.

But if fears can be inherited through epigenetics, then it is reasonable to imagine that the (de)activation of certain genes could also have an impact on traits of character that were acquired through someone's early life. A more combative attitude can be acquired by children raised in a particularly competitive environment. We could even imagine that children trained to develop their memory would activate genes that increase neurotransmitters required for memory, and that their offspring would consequently benefit from an increased memory before they even start their own drill. The same could be true for physical abilities or even some forms of intelligence linked to more active genes of some kind.

It has been observed for a long time that some abilities run in families. Parents who are good at music tend to have children who are also good at music. Many lawyers have children who also become lawyers. It could be due to their childhood environment or to genetic predispositions towards some aptitudes. In the latter case it was almost always assumed that the increased abilities lied in the genetic code itself, in other words whether someone possessed or not a particular genetic variant or mutation, and that these were purely inherited by chance from one's numerous ancestors. But in some cases it may be that our parents or grandparents are the ones to thank for (or pity, in the case of trauma). Without their own personal experiences some of our genes would never have been (de)activated, and we would not have the same character or abilities.

Acquired trauma, such as PTSD, can have a devastating effect on someone's life. It is even worse if it is inherited by a person's children and grandchildren. Fortunately we ma soon have a way to remedy to that. The understanding of epigenetic mechanisms have already prompted researchers to develop drugs that can tweak epigenomes to get rid of these undesirable changes in our DNA.

Even though the Lamarckian model of evolution was discredited as soon as it was proposed by the French scientists in the 18th century, the concept may make a come back thanks to new discoveries in the field of epigenetics. Two months ago, Brian G Dias & Kerry J Ressler published a paper in the journal Nature, in which they explain that mice whose father or grandfather learned to associate the smell of cherry blossom with an electric shock became more nervous than mice in the control group when exposed to the same odour, even though they never received the electric shock themselves. You can read about it in more details here.

If the study can be replicated with other stimuli and other animal it would mean that acquired fears, and by extension also memories, behaviours or even abilities can be inherited. This can be explained by the activation or deactivation of some genes through the process of DNA methylation and histone modification, which are the basis of epigenetic inheritance. Genes can be made more 'reactive' or 'sensitive' to stimuli, or conversely 'silenced' during an individual's life, due to a repeated exposure or behaviour, or due to a traumatic event. These changes are henceforth inherited by later generations, although they will weaken at each new generation and return to 'normal' after a few generations if the stimuli that caused the methylation are not repeated by the offspring.

There are been many human cases of apparently inherited fears or trauma, running in families for several generations, that were left unexplained by science. This could be for instance an irrational fear for the noise made by air raid sirens among children of young individuals (who hadn't had children yet) who experienced traumatic fears during air raids in WWII.

But if fears can be inherited through epigenetics, then it is reasonable to imagine that the (de)activation of certain genes could also have an impact on traits of character that were acquired through someone's early life. A more combative attitude can be acquired by children raised in a particularly competitive environment. We could even imagine that children trained to develop their memory would activate genes that increase neurotransmitters required for memory, and that their offspring would consequently benefit from an increased memory before they even start their own drill. The same could be true for physical abilities or even some forms of intelligence linked to more active genes of some kind.

It has been observed for a long time that some abilities run in families. Parents who are good at music tend to have children who are also good at music. Many lawyers have children who also become lawyers. It could be due to their childhood environment or to genetic predispositions towards some aptitudes. In the latter case it was almost always assumed that the increased abilities lied in the genetic code itself, in other words whether someone possessed or not a particular genetic variant or mutation, and that these were purely inherited by chance from one's numerous ancestors. But in some cases it may be that our parents or grandparents are the ones to thank for (or pity, in the case of trauma). Without their own personal experiences some of our genes would never have been (de)activated, and we would not have the same character or abilities.

Acquired trauma, such as PTSD, can have a devastating effect on someone's life. It is even worse if it is inherited by a person's children and grandchildren. Fortunately we ma soon have a way to remedy to that. The understanding of epigenetic mechanisms have already prompted researchers to develop drugs that can tweak epigenomes to get rid of these undesirable changes in our DNA.